Basic Neurobiology#

Now that we know some fundamentals of probabilistic modeling and inference, let’s learn a little bit about neurobiology.

Anatomy of a neuron#

Fig. 2 Anatomy of a neuron. (From Khan Academy.)#

Neurons are cells too! They have the usual list of cell parts — a cell body, nucleus, etc. — but they also have a few unique parts that allow them to communicate with one another:

dendrites: receive input from other neurons

axons: propagate electrical activity long distances

axon terminals: send signals to other neurons

myelin sheath: speeds signal propagation along an axon

Ions and concentration gradients#

Fig. 3 The difference in ion concentration inside the cell versus outside gives neurons an electrical charge. (From Khan Academy.)#

Neurons are electrically excitable cells that contain an ionic soup of charged atoms like sodium, potassium, and calcium, which together maintain a difference in electrical potential between the inside and the outside of the cell membrane [Luo, 2020].

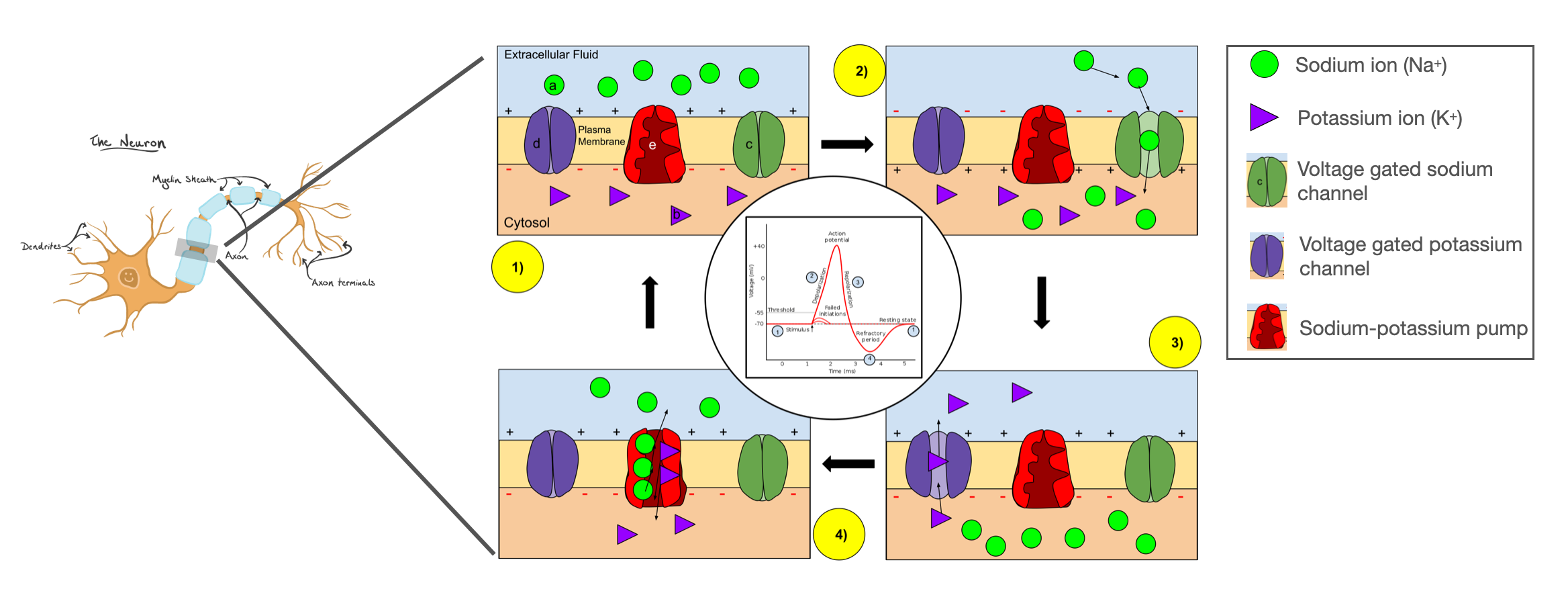

Action potentials#

Fig. 4 Voltage-gated ion channels open and close to produce a brief spike in voltage called an action potential. (Adapted from Wikipedia.)#

In most neurons, the cell membrane is littered with voltage-gated ion channels. If the membrane potential is excited above a certain threshold, some channels start to open, initiating an action potential. As described in the seminal work of [Hodgkin and Huxley, 1952], positively charged sodium ions are first to rush into the cell, causing a further increase in membrane potential and leading more channels to open. The upswing in membrane potential eventually causes a reversal in cell polarity and the inactivation of sodium channels. At the same time, potassium channels open, allowing an efflux of positively charged potassium ions. Together, these halt the rising membrane potential and drive it back down toward its resting state. This brief action potential, or spike, takes place in just a few milliseconds.

Multi-compartment models#

Of course, this spherical cow model of a neuron is not a faithful representation of biology. Neurons have a complex anatomy of axons, cell bodies, dendrites, etc., as we saw above. However, this simple model is not a bad approximation for a single compartment of a cell, like a short stretch of axon. A more realistic model of a neuron is a network of compartments, each with its own ion channels, connected via passive cables.

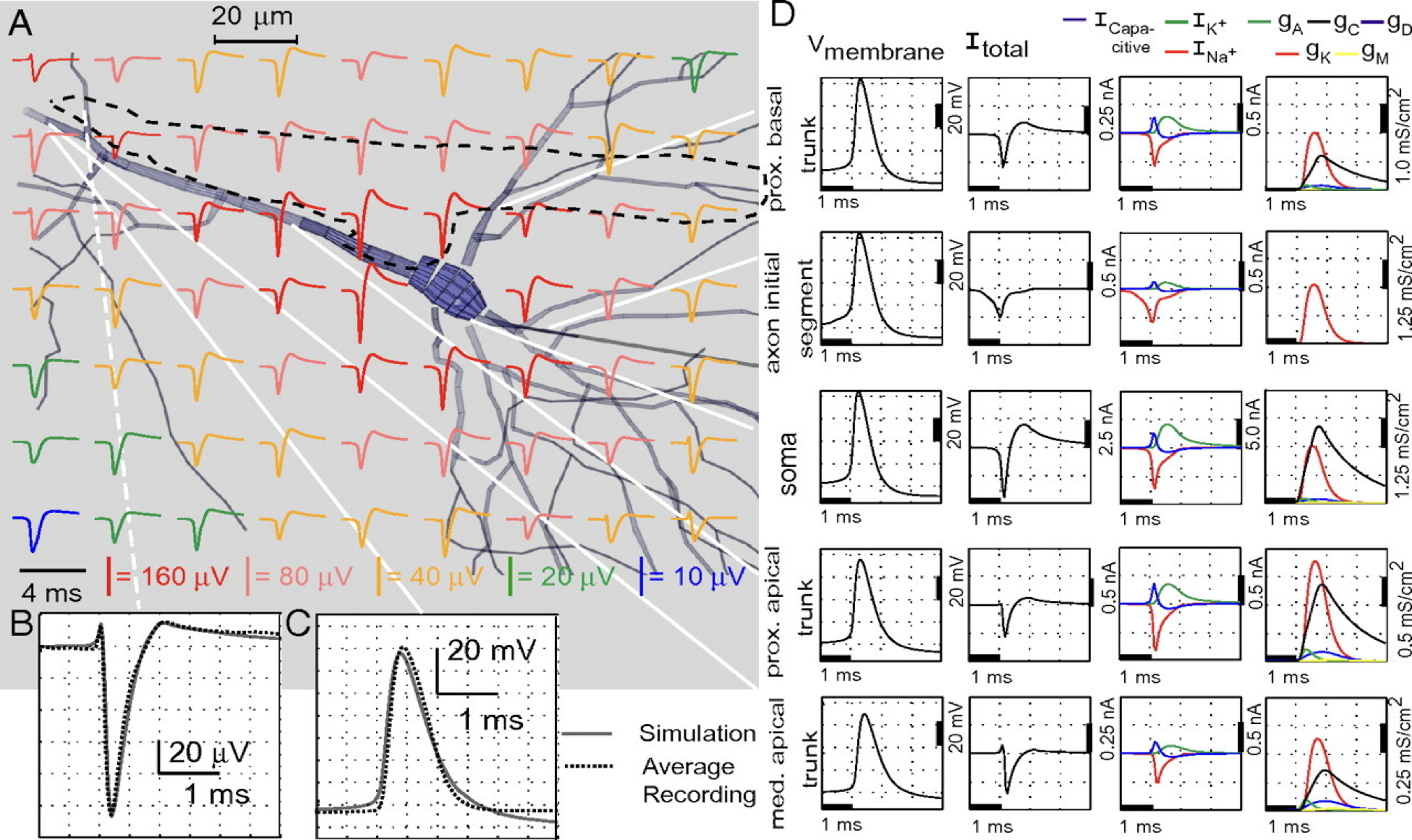

Extracellular voltage recordings#

The models above simulate how the membrane potential changes over time during an action potential to produce the characteristic spike shape. However, when we insert an electrode into the brain and measure voltage, we are typically recording the voltage at a location outside the cell in the extracellular milieu.

Fig. 5 Simulated extracellular action potential recordings from Gold et al. [2006].#

Inside the cell, the membrane potential spikes by 50-100 mV during an action potential. Outside the cell, the measured extracellular action potential (EAP) is roughly proportional to the total current in nearby compartments of the cell. The EAP typically shows a triphasic response with a sharp negative deflection of 50-100 \(\mu\)V (three orders of magnitude smaller in magnitude). The amplitude falls off with distance from the cell.

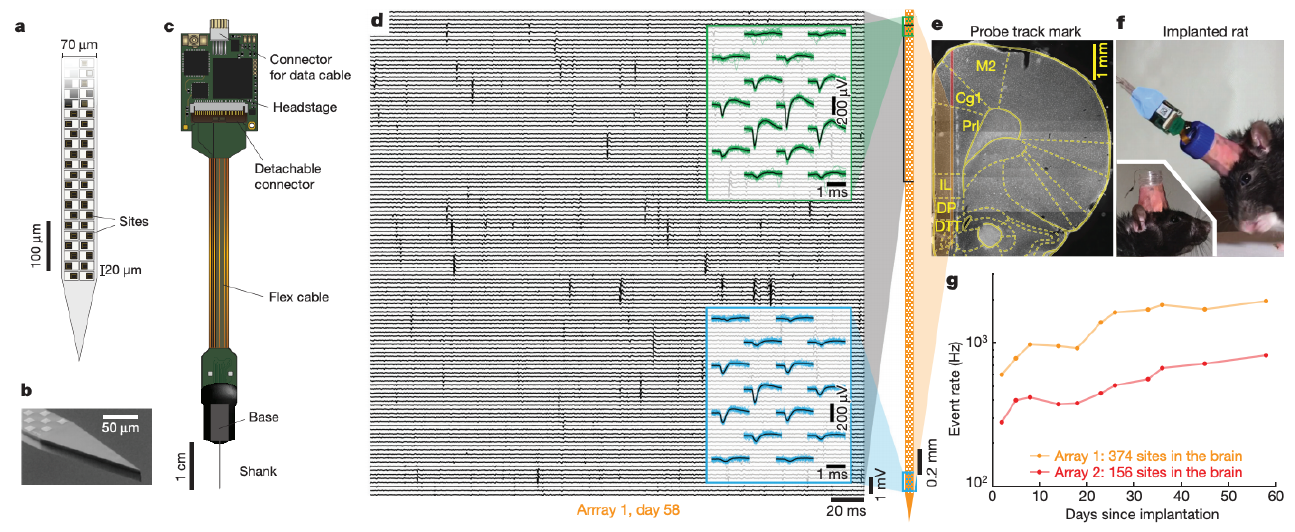

Neuropixels#

Fig. 6 a-c: Schematic of a Neuropixels probe. d. 200 ms window of the voltage time series illustrating several spikes. Insets show the waveforms of spikes from neurons near the top and bottom of the probe. e. The location of the probe with brain regions superimposed. f. Image showing the implant. g. Firing rate (summed over all neurons) detected vs days since implantation. (Adapted from fig. 1 and 4 of [Jun et al., 2017].)#

A fundamental challenge of computational neuroscience is understanding how information is encoded in patterns of coordinated spiking activity across neural circuits. To meet this challenge, we need to be able to record the spiking activity of large populations of neurons. Modern electrodes allow us to do just that. For example, Neuropixels probes [Jun et al., 2017, Steinmetz et al., 2021], shown in Fig. 6a-c, have hundreds of recording sites, or “channels.” The probe is inserted into an animal’s brain by surgically removing part of the skull to gain access to neural tissue (Fig. 6f). Once inserted, the probe can record time series of electrical potentials (voltages) at up to 30 kHz across \(\approx\)300 channels simultaneously (Fig. 6d). Neuropixels span multiple brain regions in a rodent (Fig. 6e) and are stable over months of recording (Fig. 6g). They have quickly become a popular tool for measuring brain activity.

Conclusion#

This was an admittedly brisk tour through the basics of neurobiology, but it will suffice for our discussion of spike sorting in the next chapter. We introduced

The basic parts of a neuron (dendrites, cell body, axons, etc.)

How differences in ion concentration inside vs outside the cell give rise to a difference in electrical potential

How voltage-gated ion channels in the cell membrane open and close to alter relative ion concentrations, and hence the voltage across the cell membrane

These ion channels determine a nonlinear dynamical system called the Hodgkin-Huxley model, which models how action potentials, aka “spikes,” are generated

Action potentials look nearly inverted in extracellular recordings, like those measured with Neuropixels probes.

Further reading#

If you want to learn more, I recommend:

The first few chapters of [Luo, 2020] (Prof. Luo is a professor in the Stanford Biology department and he teaches an excellent class on neurobiology!)

The first few chapters of [Dayan and Abbott, 2005] are a good primer for those coming from math, physics, and more computational disciplines.